Cardiac arrest in the operating theatre is a rare but critical event that demands quick thinking and seamless teamwork. Unlike other hospital areas, patients in surgery are already under close observation, connected to monitors, and often under anesthesia, which can mask early warning signs. When the heart suddenly stops, everyone in the room must respond instantly and in harmony. The anesthesiologist manages the airway and medications while the surgical team focuses on stopping bleeding or correcting the cause. Every person has a clear role, and clear communication can mean the difference between life and death. Preparation, practice, and coordination help the entire team act calmly and effectively when seconds truly matter.

Causes of Cardiac Arrest in the Operating Theatre

Cardiac arrest in the operating theatre can happen for many reasons, even when everything seems under control. Knowing the possible causes helps the team act fast and treat the problem at its source.

1. Anesthetic-Related Causes

- Drug Overdose or Allergic Reaction: Certain anesthetic drugs can cause severe allergic responses or overdose effects that lead to sudden cardiovascular collapse.

- Airway Obstruction or Ventilation Failure: Blocked airways or issues with the breathing circuit can reduce oxygen delivery and result in hypoxia.

- Malignant Hyperthermia: A rare but life-threatening reaction to anesthesia that causes extreme muscle stiffness, high body temperature, and rapid heart failure.

- Hypoxia or Hypercapnia: Low oxygen or high carbon dioxide levels in the blood can disturb the heart’s rhythm and lead to cardiac arrest.

2. Surgical Causes

- Major Blood Loss or Hypovolemia: Heavy bleeding during surgery can drastically lower blood volume, reducing the heart’s ability to pump effectively.

- Air or Gas Embolism: Air or gas entering the bloodstream can block circulation to vital organs, causing sudden cardiovascular collapse.

- Cardiac Tamponade: Fluid or blood collecting around the heart can compress it, preventing proper filling and pumping.

- Surgical Trauma to Vital Organs: Accidental injury to the heart, lungs, or major blood vessels during surgery can trigger cardiac arrest.

3. Patient-Related Factors

- Pre-Existing Cardiac Conditions: Patients with heart disease, arrhythmias, or previous heart attacks have a higher risk of cardiac arrest during surgery.

- Electrolyte Imbalances or Metabolic Derangements: Abnormal levels of potassium, calcium, or acid-base balance can disrupt the heart’s electrical activity and lead to arrest.

Reversible Causes of Cardiac Arrest in the OT

During surgery, it is important to quickly identify and treat causes that can be reversed. The standard Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) “Hs and Ts” help guide the team, but they are adjusted for the operating theatre environment.

- Hs: Hypoxia, low blood volume, acidosis, abnormal potassium levels, and low body temperature can all trigger cardiac arrest and need prompt correction.

- Ts: Tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, toxins, and blood clots in the heart or lungs are critical issues that require immediate attention.

Examples of OT-specific reversibility:

- Heavy bleeding can cause hypovolemia

- A gas embolism may block blood flow

- Surgical manipulation can trigger vagal responses

Also, Read: Reversible Causes of Cardiac Arrest

Early Recognition and Prevention of Cardiac Arrest

Noticing warning signs early can make a big difference when a patient’s heart is at risk. Staying alert and taking quick action helps prevent cardiac arrest before it happens.

- Continuous Intraoperative Monitoring: Keep a close watch on ECG, capnography, pulse oximetry, and blood pressure to detect any early warning signs. Strong ECG rhythms recognition and interpretation for ACLS skills are essential here, helping clinicians identify subtle changes before they become critical.

- Identifying Warning Movements: Look for changes in heart rate, oxygen levels, or blood pressure that may signal a risk of cardiac arrest.

- Team Communication: Maintain clear and constant communication between the anesthesia and surgical teams to act quickly if a problem arises.

Immediate Response and Team Roles in the OT

When cardiac arrest happens in the operating theatre, teamwork becomes vital. Each member of the team has a clear role to help the patient quickly and safely.

- Role of the Anesthetist: Recognize cardiac arrest, secure the airway, manage breathing, give emergency drugs, and coordinate resuscitation efforts.

- Role of the Surgeon: Stop the surgical procedure if possible, control bleeding, and address any reversible surgical cause of the arrest.

- Role of the Nursing and Support Staff: Bring emergency equipment and medications, assist with chest compressions, monitor vital signs, and document all actions clearly.

Performing CPR in the Operating Theatre (OT)

Performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the operating theatre is different from other areas and requires quick consideration and teamwork. The team must adapt standard techniques to the patient’s position and the surgical environment to give the best chance of survival.

1. Modifications Due to Surgical Positioning and Sterility:

1a. Supine Vs. Prone Position

When the patient is lying on their back, CPR is similar to standard practice, and compressions can be done in the usual way. If the patient is prone, the team may need to adjust hand placement or carefully turn them to perform effective compressions while keeping the surgical area safe.

1b. Lateral or Sitting Position

For patients lying on their side or sitting up, chest compressions require careful positioning of hands and body to maintain effectiveness. The team works together to ensure compressions are strong and steady without disrupting the surgery or sterile field.

2. Chest Compressions:

2a. When and How to Perform Compressions in Non-Supine Patients

If the patient is not lying on their back, compressions can still be effective with adjusted hand placement and body positioning. The team may press on the back or side of the chest, depending on the patient’s position, while keeping the movements steady and firm.

2b. When to Resume Compressions If Surgical Access Is Required

If surgery needs to continue or the surgical field blocks compressions, the team pauses only briefly and resumes compressions as soon as it is safe. Clear communication ensures compressions restart quickly without delaying care or harming the patient.

3. Defibrillation:

3a. Use of Defibrillator Paddles in the Sterile Field

When defibrillation is needed, paddles can be carefully applied without contaminating the sterile area. The team positions the paddles to reach the patient safely while keeping surgical instruments and drapes protected.

3b. Safety Precautions and Placement of Pads

Ensure pads or paddles are placed correctly on the patient’s chest to deliver the shock effectively. Team members stay clear and follow safety steps to avoid accidental contact during the shock.

Also, Read: When Should the Rescuer Operating The AED Clear the Victim?

4. Airway and Breathing:

4a. Use of an Anesthesia Machine for Ventilation

The anesthesia machine helps provide controlled breathing during CPR, ensuring the patient gets enough oxygen. The anesthetist adjusts settings as needed while monitoring chest movement and oxygen levels.

4b. Ensuring Oxygen Delivery and Checking for Circuit Disconnections

It is important to confirm that oxygen is flowing properly and that no tubes or circuits are disconnected. Regular checks prevent delays in ventilation and keep the patient’s oxygen supply steady.

Special Situations During CPR in the Operating Theatre

Some cardiac arrests in the operating theatre happen in unusual situations that need extra care and quick thinking. Each scenario has specific steps to keep the patient safe while providing effective resuscitation.

1. Cardiac Arrest in Prone Patients

When a patient is lying face down, the team must act quickly to provide CPR. Compressions can be performed on the back if turning the patient is not possible, and everyone works together to keep the surgical area safe.

2. During Laparoscopic Surgery

Gas used to inflate the abdomen can sometimes enter the bloodstream and cause problems. The team carefully monitors pressure and circulation while managing any gas embolism that may occur.

3. During Cardiothoracic or Neurosurgery

In heart or brain surgeries, the team may need to perform open cardiac massage or use internal defibrillation. These steps are done quickly and carefully to restore circulation without delaying the procedure.

4. Pediatric or Obstetric Surgery Considerations

Children and pregnant patients have special needs during CPR. The team adjusts compression depth, positioning, and drug doses to ensure safety while providing effective resuscitation. Knowing guidelines of ACLS in-hospital cardiac arrest in pregnancy algorithm is crucial.

Post-Resuscitation Care in the Operating Theatre

After successful resuscitation, the focus shifts to keeping the patient stable and preventing another crisis. Careful monitoring, clear communication, and thorough documentation help ensure a smooth recovery and safe transfer.

1. Stabilization Before Transfer to the ICU

After successful resuscitation, the patient needs to be stabilized before leaving the operating theatre or ICU (intensive care unit). The team ensures the airway, breathing, and circulation are secure and that vital signs are steady for a safe transfer.

2. Monitoring and Correcting Underlying Causes

The team continues to watch the patient closely and addresses any problems that caused the arrest. This may include managing bleeding, adjusting medications, or correcting electrolyte imbalances to prevent another crisis.

3. Documentation of Intraoperative Events and Drug Doses

Accurate records of what happened during the arrest are essential. This includes noting the timing of events, drugs given, and any interventions, which helps guide future care and supports team accountability.

4. Communication with the ICU and Family Members

Clear updates are shared with the ICU team to ensure continuity of care. The family is also informed compassionately and honestly about the patient’s condition and what occurred during surgery.

Also, Read: Immediate Post-Cardiac Arrest Care

Training, Simulation, and Team Preparedness

Being ready for a cardiac arrest in the operating theatre takes practice and teamwork. Regular training and clear roles help the team respond quickly and confidently when every second matters.

- Regular practice through mock drills and crisis simulations helps the team stay ready for emergencies. These exercises improve speed, coordination, and confidence when real cardiac arrests occur.

- Role-based rehearsals allow each team member to focus on their specific duties, and debriefing afterward highlights what went well and what can improve.

- Integrating ACLS protocols into perioperative training ensures everyone knows the latest guidelines and can apply them smoothly during surgery.

- Creating a culture of psychological safety encourages team members to speak up, ask questions, and learn from each event, making future responses even stronger.

The Importance of CPR During Surgery

In the operating theatre, being prepared can make all the difference. Cardiac arrest is rare but serious, and the whole team must act quickly and together to give the patient the best chance of survival. Knowing the possible causes, spotting warning signs early, and practicing clear communication help the team respond calmly and effectively. Adapting CPR to the surgical environment, identifying reversible problems, and providing careful post-resuscitation care are all essential steps. With regular training, teamwork, and a focus on preparation, the operating theatre can remain a place where patients are safe and teams feel confident, even in the most critical moments.

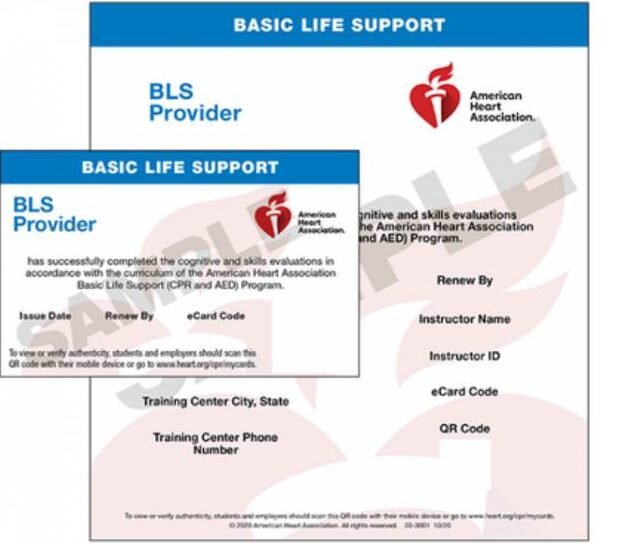

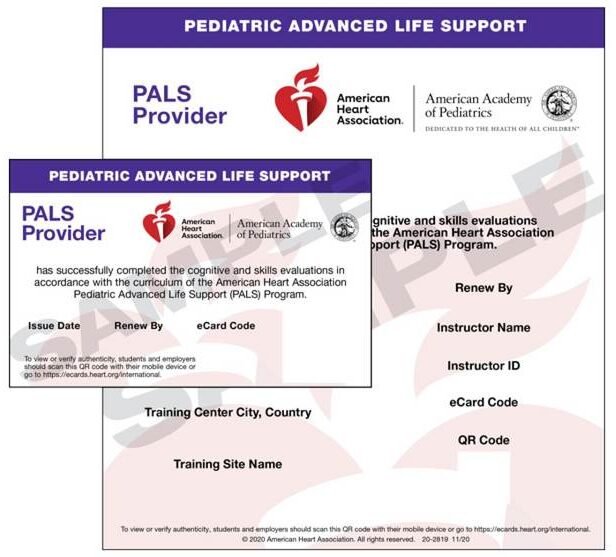

Be ready for any emergency with the convenient, flexible lifesaving courses from Bayside CPR. Prepared for busy professionals, our programs combine a short online module with a 30-minute, hands-on skills check at any of our 60+ CPR Verification Stations. Receive your American Heart Association course completion card in BLS, ACLS. PALS, CPR, and First Aid, and leave the same day confident, trained, and prepared to act.